By DEB SCANLON

In 1951, Charles and Margaret Spohr purchased a six-room house on two acres of overgrown wooded land looking out over Oyster Pond in Falmouth. “It was just a small house surrounded by a jungle,” Mr. Spohr recalled in a 1989 Enterprise article. They gradually added four more acres, where they planted gardens meticulously.

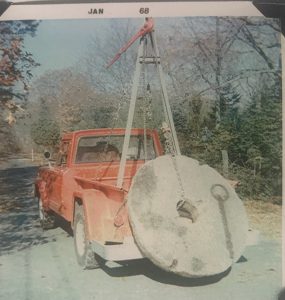

Photo courtesy Spohr Gardens Archives Charles Spohr collected millstones from old mill towns and moved them with his pickup truck to Quissett.

As the plantings flourished, the public was welcomed to view the six-acre Spohr Gardens on Fells Road. Dazzling displays of daffodils in the spring, followed by azaleas, rhododendrons, day lilies and trees ranging from magnolias, weeping beech, Japanese umbrella pines to American hollies drew thousands of visitors.

Neither Charles nor Margaret had professional experience in gardening. As Hila Lyman, chairperson of the Spohr Gardens board of trustees, said, “It’s amazing that Spohr Gardens were created by a nurse and an engineer.”

Margaret Ellen King Spohr was a graduate of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. During World War II she served as a second lieutenant in the US Army Nurse Corps and later continued her nursing career at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

Charles D. Spohr was born in New Jersey, and he and his family spent summer vacations in Centerville. A graduate of Virginia Military Institute with a degree in civil engineering, he entered the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1938. He participated in the Normandy invasion and was later seriously injured at the Siegfried Line in Germany. He and Margaret met at the Mayo Clinic, where he was recovering from his wounds. They married in 1946.

In May 1951 the Enterprise reported that the Spohrs had bought a home on Fells Road in Quissett from Wilbur A. Dyer. The house was built in 1938, designed by Falmouth architect E. Gunnar Peterson for two Boston women, who later sold it to Mr. Dyer.

GEORGE CHAPMAN

The Spohrs would spend their winters going through garden catalogs, Ms. Lyman said. “Margaret kept good records of the cultivars and it is possible to still order some of the species that she ordered. “Charlie was very frugal and he didn’t want to spend money on annuals,” so they only ordered perennials. The Spohr Gardens archive has the original designs that Margaret created for the gardens and the logbook of all her purchases.

Margaret designed the flower beds and was “way ahead of her time, planting the bulbs in swaths to give them more impact,” Ms. Lyman said. “Today, landscape architects plant in swaths of a single cultivar—it’s pretty much the norm. But Margaret didn’t have any training and she did it back in the 1970s—way before it was popular.”

Charles used his engineering skills to design the wells and irrigation system. He also created the paths that wind through the gardens, using cobblestones from the streets of New Bedford. He enjoyed collecting anchors and millstones and displayed them as “decorations” throughout the gardens. There are at least 75 millstones throughout the property that had been used in mills to grind everything from wood pulp to corn to mustard. They range in size from six inches to eight feet in diameter. He purchased some and others were given to him if he would haul them away.

GENE M. MARCHAND

“You’d think it would be cluttered but it is not. He was very creative,” Ms. Lyman said.

The collection of antique anchors lines the shoreline of Oyster Pond. A favorite of Charles’s was an anchor originally intended for use on the HMS Bounty, but after finding faults with the anchor it was left ashore as the ship slipped into history. The 2,475-pound anchor is 14 feet long and has eight-foot arms.

Other decorations Charles collected include a large church bell made in 1882 that sits among the daffodils, a smaller bell that is near the water and lighthouse lanterns with lenses from Paris that are on the patio.

Charles had several gardeners on staff to take care of the gardens. In 1989 Michael Kadis was hired, and he later helped maintain the house in addition to his gardening responsibilities. He became caretaker, a position he still holds.

GEORGE CHAPMAN

Charles Spohr used his collection of millstones and anchors as decorations throughout the gardens.

The Spohrs set up the Spohr Charitable Trust to maintain the garden in perpetuity and keep it free and open to the public. Charles also wanted to be sure his wife, who was disabled, would be able to live at home the rest of her life. He was 83 when he died in 1997; she died at the age of 85 in 2001.

The mission to maintain the gardens, however, became more challenging, Ms. Lyman said: “All the plants grew higher, and in the last five years the daffodils started to die out. The trees were too high and were taking nutrients away from the daffodils. Now what?”

George Chapman, the gardens’ volunteer coordinator since 2019, went through old photos and what struck him was how much more open the fields used to be. He started pruning rhododendrons and other shrubs, allowing more light into the gardens as well as a better water view. He began replanting the daffodils at the rate of approximately 1,000 bulbs a year.

“We have planted 3,400 bulbs thus far in our rejuvenation program,” Mr. Chapman noted, “and there are probably another 1,000 that continue to bloom from past plantings by the Spohrs. Not a huge number of bulbs at present, but combined with the rolling hills, winding paths, azaleas, rhododendrons and Oyster Pond, a magical spring scene is created.”

Mr. Chapman has also planted a pollinator pathway, not just for monarch butterflies but for all pollinators.

“Our most ambitious project was the renovation of the front of the garden along Fells Road. Vistas were opened up, information boards added, and the two largest and most decorative millstones of Charlie’s collection were moved from the private driveway to the front of the garden for all to enjoy,” Mr. Chapman said.

Spohr Gardens are still free and open to the public every day from 8 AM to 8 PM.