In the year 1460 two Portuguese captains, returning in their ships from a cruise down the African coast, were blown offshore. They discovered a group of uninhabited volcanic islands, between 300 and 400 miles west of Cape Verde, the westernmost point of Africa.

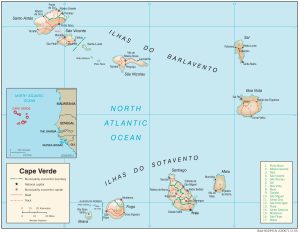

The Cape Verde Islands.

“Islands lost in the middle of the sea,” the poet Jose Barbosa was to call them.

“Islands lost in the middle of the sea,” the poet Jose Barbosa was to call them.

From their blunt-nosed caravels, rocking in the Atlantic swell, the Portuguese mariners surveyed the rugged island landscape, quiet, save for the birds, with the stillness of creation. Jagged volcanic peaks rose abruptly from the sea, desolate and barren. Only in the valleys which trapped the infrequent rain was there a lushness of vegetation, the exuberant and violent growth of a tropical forest.

The Portuguese discoverers would have noted the presence of the wind, the steady beat of the trades that has impressed every visitor since. The wind is always there. In January and February, the wind is cruel; easterly winds from the African continent which are called the “Lestadas.” They carry to these already arid islands the heat and dust of the Sahara.

The wind as a malevolent force has fixed itself in the Cape Verdean consciousness. The Cape Verdean writer Manuel Lopes called his novel “Os Flageladoes do Vente Leste”—victims of the cruel east wind.

Immigrants at New Bedford in the 1920s. Most of those shown in this old newspaper photograph are Cape Verdeans. At the height of immigration only about 1,500 Cape Verdeans a year entered the United States, mostly at New Bedford and Providence. Most of them crossed the Atlantic in wooden vessels smaller than those of Christopher Columbus.

Portugal was expanding across the oceans. Twenty years earlier it had begun settlement of the Azores. It had peopled Madeira. It found a use for the Cape Verde Islands. They were on the direct trade route to Africa and India. They were conveniently close to the great circle route to South America.

The explorer Cabral stopped at the Cape Verdes on his way to Brazil.

The Portuguese colonization of Sao Thiago began in 1462.

A Cape Verdean once observed ruefully that his people are “caught in the middle” in the polarization of Americans, Black and white. It is true, for the Cape Verdeans are uniquely neither. A few Blacks remain in the Cape Verdes, their African blood unmingles. But the great majority of Cape Verdeans are the result of a centuries-old mingling of Portuguese, with a strong Moorish strain, and African. In the isolation of these islands the mixture had centuries in which to develop its unique character. The world has no other people just like them.

The early Portuguese colonists, mostly from the southern province of Algarve, brought slaves from Guinea and Sierra Leone in Africa. There was a heavy leavening of Jewish blood. The Inquisition was driving Jews from Portugal.

The Portuguese settlers came from all classes. There is some proud cavalier blood in the Cape Verdeans. Early development of the islands was accomplished under an imported feudal structure.

Praia, Cape Verde

Portuguese power eventually collapsed. The islands were left to shift for themselves. Plantations were scraped out of the arid soil. For a hundred years the islands were a resort for pirates and buccaneers, who used and plundered and destroyed. Yellow fever, small pox and malaria came with the earliest settlers, and they flourished. Pillage and neglect, disease, drought, famine, these were the scarifying and brutal forces that shaped a hardy people. The people continued to exist, scratching their living from the land, taking it from the sea, improving it occasionally by trade with call ships.

They went on like this for several hundred years, in the remote isolation of their islands, in the buffeting of the wind and the ceaseless surge and pounding of the sea.

Then came the

Yankee whalers.

New England discovered the Cape Verdes, and the Cape Verdes discovered New England. It was a mutual recognition. The whalers beat across the ocean and put into the Cape Verdes for water and for fresh vegetables and—increasingly—for seamen to fill out their crews.

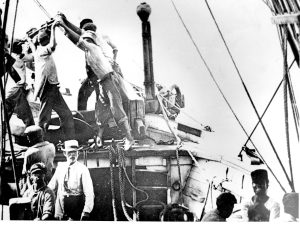

Cape Verdeans sailed in the crews of New Bedford whalers as early as the 1840s. In the last years of the whaling industry, most of the whalemen were Cape Verdeans. The New Bedford Whaling Museum provided this photograph taken on board the brig Daisy, Captain D.D. Cleveland, in 1912.

A plaque in the Seamen’s Bethel at New Bedford shows there were Cape Verdeans among the whaling crews as early as 1847. These islands made good seamen.

The Verdes met a need of the whaling fleet, and the whalers met a need of the Cape Verdeans, the need to escape from their hard islands, from a homeland that Cape Verdeans down to the present day have regarded with a painful mixture of love and despair. It was a Cape Verdean who observed not long ago that every Cape Verdean is a potential immigrant.

The first Cape Verdean to set foot on New England soil stepped off a whaling ship.

It was not only men that passed between the Cape Verdes and New England. A trade developed, in salt and other island products. For many years the Cape Verdes’ trade with New England was second only to that with Portugal.

Cape Verdean settlement in America followed the whaling fleet; first to New England, then to California and Hawaii. These are the centers of Cape Verdean-American population today.

The whaling industry died, but it had established the connection between New England and the Cape Verdes. It was more than a business connection. A sympathy had been established. When one of the worst famines descended on the Cape Verdes in the 1830s, New Englanders sent food.

The Cape Verdeans now could see something beyond the wide sea horizon. An ocean path, 3,600 sea miles long, stretched from the Cape Verdes to New Bedford.

It became a

well-traveled path.

The Cape Verdes are an archipelago, at their closest 283 miles off the African coast, on the latitude of Dakar; and the latitude of Puerto Rico.

There are 10 islands altogether, and five islets, divided into the Leeward and Windward groups.

They are scattered over a wide piece of ocean. Brava to the southwest is 170 miles from Sao Antao in the northeast. Brava is the smallest, about the size of Nantucket. Foro is four times the size of Martha’s Vineyard. Sao Thiago is twice again as large. There is room to move around on these islands.

Five hundred years after the Portuguese captains had found them uninhabited, the Cape Verdes contain 550,000 people.

Developing as a distant people, the Cape Verdeans developed a language, the vernacular called crioulo. It was influenced by the tongues that the Africans brought with them. One authority said that crioulo is unintelligible to natives of the Azores or of mainland Portugal. But the literate Cape Verdean will understand Portuguese. He used to call it “royal Portugese.” He will probably speak it fluently.

Most of the Cape Verdean Americans came from Brava and Fogo. These islands are within sight of one another.

Brava means “wild.” It was settled late, in 1680. There is a tradition that its settlers were fugitives from the other islands that were being pillaged by pirates and slavers.

One hundred years ago, and perhaps today, Brava was called the “paradise of the Cape Verdes.” The feudal system had never been imposed there. Bravas owned their own land, however meager the patches. Bravas have always excelled in reading and writing.

Brava islanders were always closer to the sea than the others. Everyone agrees that the Bravas made particularly good seamen.

Fogo means fire. Fogo has its own peculiar and spectacular affliction of nature, the volcano Pico do Cano, which has erupted with disastrous results. St. Philip is the capital of Fogo. Coffee was raised there years ago, and ponies.

A century ago, a man who knew the Cape Verdes said the people there lived pretty much as their ancestors had learned to live when Columbus was still sailing the ocean.

Probably the largest vessel in the Cape Verdean packet traffic was the iron bark Coriolanus, shown here under tow, departing New Bedford. The photograph was provided by the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Coriolanus had a long earlier career under the names Tiburton, Eugenia Amelia and lina. She sailed from New Bedford to Praia with a cargo of various provisions, lumber and oil, commanded by Captain H.W. Hammett of Chilmark, a veteran whaleman. Coriolanus served as a Cape Verde packet from 1923 until she was broken up for scrap in 1937.

The Cape Verdeans came to this shore, by and large, to do the meanest labor, escaping from their harsh poverty by the only means open to them, and it is not surprising that the alien race among which they settled, seeing their poverty and not comprehending their language, had not discovered Cape Verdean literature.

Early in the course of Cape Verdean immigration, it was noticed that Cape Verdeans were generally more literate than immigrants from the other Portuguese islands. “One has only to examine the manifest of a Cape Verde packet to appreciate what good penmen there are among them,” one observer wrote.

It is a remarkable fact that the people of the Cape Verdes, oppressed by nature and every circumstance, became a prolific literary people. This hunger for letters was their own. It was not given them by the mainland Portuguese, fewer of whom proportionately learned to read and write.

Norman Araujo’s parents were born on the island of Sao Nicolau. When he was at Boston College in 1966, Mr. Araujo wrote a study of Cape Verdean literature.

Cape Verdean literature, as Araujo put it, “developed painfully, irrepressibly, defying the dryness of the soil and the bleakness of the future.” Cape Verdean literature has been an exercise in sheer willpower.

Araujo sketches against the unlikely background of isolation, poverty and hunger his picture of young Cape Verdeans at the seminary, indigent professors somehow scraping together the pennies for foreign texts, students walking many miles to classes.

A Cape Verdean wryly observed that literacy is not to be confused with having enough to eat.

Cape Verdeans have overcome the meagerness of island life to make their mark in various fields. Simplicio Joao Rodrigues de Brito was a famous 18th century painter at the court in Rio de Janeiro. Robert Duarte Silva taught chemistry in Paris, so distinguished a teacher that there is a statue of him there. Candido dos Reis was an admiral and one of the founders of the Portuguese republic, following the last of the kings in 1910. Manuel Peres Sacramento Monteiro became a judge of Portugal’s supreme court. Joao Burnay became a successful industrialist.

From the islands of the Cape Verdeans brought old customs. The “canta riss” comes at the New Year, when men and women go from house to house, playing and singing, bringing good wishes of the season.

They brought from the islands the tastes and customs and memories that constitute a culture. They brought their “feiticeiros,” ghost stories rooted in ancient memory. They brought their taste for traditional island dishes, “manchupa” and “canja” and others, relying heavily on chicken and vegetables.

They brought their religion and their festivals. Their Feast of St. John the Baptist in June celebrates the time long ago when prayers to St. John resulted in a rainfall that broke a drought.

There is a community feast, and each year one family has the honor of erecting the banner, the red cross of St. John on a white field. The banner flies at the top of a mast, carved for the occasion and decorated with streamers. In Falmouth last June, the banner was raised at the home of Mrs. Mary Santos on Sandwich Road. Her son, Julio, spent three or four hours fashioning the mast from a 30-foot piece of oak.

The feast of Santa Cruz on May 3 is a similar occasion.

The modern immigration of Cape Verdeans into New England began in earnest around the turn of the last century. Compared to what was going on at Ellis Island, it didn’t amount to much, from 1,000 to 1,500 immigrants a year. But they were all coming to one small corner of Massachusetts.

The modern immigration of Cape Verdeans into New England began in earnest around the turn of the last century. Compared to what was going on at Ellis Island, it didn’t amount to much, from 1,000 to 1,500 immigrants a year. But they were all coming to one small corner of Massachusetts.

In 1905 the people of Cape Cod and nearby towns in Plymouth and Bristol counties were startled to discover that they had a race problem.

In Harwich there was agitation for segregated schools. In Marion an article was placed in the Town Meeting warrant directed against further employment of Cape Verdeans on town works.

The hostility toward the Cape Verdeans in some quarters caused people to take a closer look at these new neighbors.

The New Bedford Standard described them as an “element that must be reckoned with, socially, industrially and educationally.”

It was noted that the Cape Verdeans were peaceable and, in their own tongue, literate. It was also noted that they were industrious and thrifty.

“It is pretty evident hereabouts,” said the New Bedford Mercury, “that the time is not far distant when they will own all the farms in the surrounding country, and that they are the thriftiest element in our population.” What the Yankees liked particularly was that they paid their bills.

The confrontation of 1905 was the product of a unique immigration. The Cape Verdeans did not cross the ocean in the steerage of ocean liners. They crossed in little wooden hulls. The passage was long and lonely. It tested their courage in a particular way. It was the heroic age of the Cape Verde packets.

The packets were a fleet of small sailing vessels that went between the Cape Verdes and New Bedford and Providence. Most were former New England fishing vessels or small coastal schooners. It is recalled that one was a former luxury yacht, Ramona. The numbers varied from year to year. In 1905 there were a dozen packets in service. They were not only small. They were inevitably in poor condition when they went into service, nearly worn out by use and available cheap.

Most of them had

Brava skippers.

“These Brava captains were first-class mariners and splendid navigators,” said one authority. “They had plenty of nerve. There was great rivalry among them to make quick passages. They virtually raced these old worn-out vessels across the Atlantic, like an ocean yacht race. Each kept secret his own idea as to where it was most advantageous to leave the trades and steer north into the “variables” when coming out in the spring.

“In the autumn they often started back with deck-loads of lumber. Sometimes they were never heard of again, after leaving port. I can recall four or five that were lost with all hands, but Brava islanders seemed to look on such incidents as part of the game.”

The first Cape Verdean immigrants were mostly Bravas, and they mostly went to work on the water. The quartermasters and most of the crews of the Fall River Line steamers were Cape Verdeans. In Providence it was said that Bravas had “driven out most of the native sailors and now man every barge or schooner that comes to port or leaves it.”

The cranberry growers provided the impetus for the larger later immigration.

The immigration has continued in a small way down to the present. In 1969 the United States issued 281 immigrant visas to Cape Verdeans.

Passenger traffic on these crowded Cape Verde vessels was not attended with the sickness that occurred on old immigrant ships in the North Atlantic. The voyages were made in a warmer climate. A surprisingly small number of immigrants from the Cape Verdes were found by us on arrival to have the diseases known to be common in the islands.

The Cape Verdean immigrants did not remain healthy under conditions imposed in their new home. Sickness and mortality were high, especially in the barracks or the cranberry bog shacks in which they were housed immediately after arrival. Sick and destitute Bravas, as they were called, were constantly being brought to the attention of immigration officials. These warm-climate immigrants did not know how to protect their health under agricultural working conditions in a climate that was new to them. They did not adjust to the unaccustomed diet that was needed to keep up their strength and resistance to disease. Crowded into unsanitary shacks, they died like flies from pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Belmira Nunes Lopes was one of the first Cape Verdeans to be graduated from a high school in this country. She was valedictorian of her class at Wareham High School. With help from the community, she went to Boston University. She transferred to Radcliffe and was graduated there cum laude in 1924. For 25 years she has held responsible posts in the New York City school system.

She recalled the early years.

“Summer was for picking blueberries. The woods on the way to cranberry bogs abounded in them. The berries were sold to the boarding houses and to the neighbors, who did not care to indulge in such back-breaking activities. Or they were taken to the center and sold to the more affluent homes. The money wasn’t much, but it helped to keep body and soul together until cranberry picking time.

“In the fall more men were brought in from New Bedford and Providence to pick cranberries. My father, who knew more English than his associates, was generally sent to recruit them. They came in groups of a dozen or more to live for a month or six weeks in one-bedroom shanties near the bogs.

“Here they slept in bunks with straw mattresses arranged in double rows along one side of the shanty. Here they cooked their ‘jagacida,’ beans cooked with rice, onions and lard, or ‘cachupa,’ hulled corn with dry lima beans. Here, too, they played ‘bisca,’ a card game similar to whist.

“Wood cutting by the cord was done for a dollar a day, and cutting of ice from the ponds, to be stored in ice houses and insulated with sawdust for summer consumption.”

The Cape Verdeans had barely begun to establish themselves outside of this indentured servitude when the Great Depression came. The way has not been easy for Cape Verdean Americans. There are ways of measuring what has happened among Cape Verdeans here. One of them wrote recently that he could recall when only three Cape Verdean Americans had been to college.

This seaborne race from the Hesperides has added its own rich chapter to the American experience.