BY JOHN H. HOUGH

As the sun sank low early in the evening on Christmas Eve 1943, light shined forth from houses unadorned by blackout curtains for the first holiday season in two years. Shoppers walked the frozen main streets of the Cape, bundled against the bitter cold, the mercury having dipped below zero the previous night. A patchwork of clouds marched across the darkening sky in a gently blowing breeze.

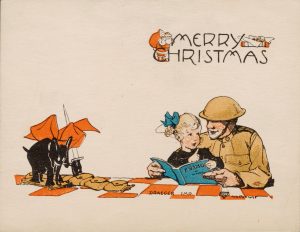

From across the globe came cards for those at home with tidings of good cheer and wishes for reunion. From North Africa and Italy, England, Australia and on small Pacific islands recently added the popular lexicon, Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tarawa.

From across the globe came cards for those at home with tidings of good cheer and wishes for reunion. From North Africa and Italy, England, Australia and on small Pacific islands recently added the popular lexicon, Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tarawa.

Houses across the Cape, in neighborhoods, along fields and seaside, displayed service flags in their lighted windows, white with a red border and a blue star for each member of the household serving in uniform. Two blue stars even adorned the ticket office of the Vineyard ferry in Woods Hole for the requisitioned steamers New Bedford and Naushon serving the war effort in Europe.

On Falmouth’s Main Street, “The Man from Down Under” staring Charles Laughton graced the Elizabeth Theater’s marquee. Moviegoers exiting the matinee shuffled out onto the sidewalk while the theater prepared the reels for the 7 PM showing.

On Falmouth’s Main Street, “The Man from Down Under” staring Charles Laughton graced the Elizabeth Theater’s marquee. Moviegoers exiting the matinee shuffled out onto the sidewalk while the theater prepared the reels for the 7 PM showing.

For the Reverend Leslie L. Baily Church, December 24, 1943, proved to be a busy one. The California native, who had presided as pastor for the Falmouth Methodist Church for only two years, performed four marriages that day with a fifth scheduled for Christmas. Young couples eagerly sought marriage before the war forced them worlds apart.

The prevailing chill drove some indoors to seek warmth in front of a fire while others braved the cold to hike, hunt and pursue the shops despite the ongoing rationing.

Ponds around the Cape froze in the Arctic weather, but police pleaded with parents to call before allowing youngsters to venture onto the ice. Kids were, after all, on school vacation until January 3. A spate of rescues in the previous weeks had prompted the warning.

The train pulled out of Falmouth Station just before 6 PM and sped into the darkening gloom toward Boston. The ailing New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad found financial reprieve in the country’s mobilization, and no doubt the train that night was not empty. Headlines splashed across that day’s papers now read aboard the swaying, clacking carriages carried word of an impending railroad strike and the president’s warnings of government intervention to keep the trains rolling.

The train pulled out of Falmouth Station just before 6 PM and sped into the darkening gloom toward Boston. The ailing New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad found financial reprieve in the country’s mobilization, and no doubt the train that night was not empty. Headlines splashed across that day’s papers now read aboard the swaying, clacking carriages carried word of an impending railroad strike and the president’s warnings of government intervention to keep the trains rolling.

A thin sliver of a moon shone weakly down on the villages of Cape Cod. As families gathered around the table that winter night, a season of light, empty places at the dining room table served as a constant reminder of the war that had upended so many lives. Some of the chairs at the table would remain forever empty. These households displayed the service banner with a gold star, a father or brother who would not return home. Others knew they would soon part for the unknown, so they took this opportunity to celebrate with friends and family in the warmth of their homes.

Hope and cheer were found in the face of upheaval and uncertainty, as people knew that one day the war would be over and life would continue. In 1943, the darkness of blackouts and warning of air raids on the Cape had passed. Locals could shine forth their holiday cheer and look forward with hope to a brighter future when they may reunite with loves ones in peace to carry on their lives once again.