By DAVE PEROS

I’ve always wondered what it is about fishing that makes veracity such an issue among those who participate in the sport and, even more so, those who don’t.

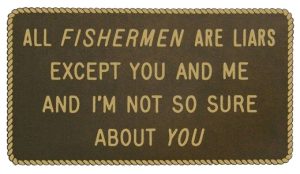

After all, renowned fishing author John Gierach even went so far as to choose as the title of one of his collections of stories this simple “indictment”: “All Fishermen Are Liars.”

The term “liar” certainly carries a heavy, judgmental air to it and I suspect that Gierach was using it to poke some fun at or smile, conspiratorially, with his fellow anglers, as opposed to questioning their sense of right and wrong.

The term “liar” certainly carries a heavy, judgmental air to it and I suspect that Gierach was using it to poke some fun at or smile, conspiratorially, with his fellow anglers, as opposed to questioning their sense of right and wrong.

But that still left me wondering about why he would even choose to use such a broad stroke when referring to his fellow members of the fishing community including, apparently, those who prefer to fly fish as he does? And by extension, what does it say about anyone who participates in any of the piscatorial arts?

At its worst fishing breeds lying, which then often turns to cheating, and that’s why many big money offshore tournaments require videotape evidence of all fish caught, from hookup to release.

Even one of the most-revered fishing contests on the Cape and islands, the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Tournament, has had its share of controversy when it comes to honor and honesty. All one has to do is read “The Big One,” a compelling tome by David Kinney that covers the history of the derby, as well as recount the controversy over a big striped bass and her belly full of lead weights and other rigging paraphernalia.

Now, while one could argue that cheating is more of a distant cousin to lying, they both involve telling the truth.

Now, while one could argue that cheating is more of a distant cousin to lying, they both involve telling the truth.

Having worked on and off at Eastman’s Sport & Tackle in Falmouth, I have been spared the challenge of dealing with the nefarious side of lying and fishing, but I have quite often heard stories that led to raised eyebrows.

The most common is how many or how big the fish are that an angler caught. Some people keep track in a logbook the number of fish they catch in a season, but how do we know that their count is accurate? And then there is my favorite: An angler comes in and states that he caught, for example, a 33-inch fish, but when asked if he measured his catch, the answer is “No.” So why offer up such a precise number? That tendency is something I never understood and is the reason I refer to fish that I catch as small, medium or large, leaving plenty of vagueness to my assessments.

Frankly, numbers are a pretty dry, dusty way to evaluate one’s fishing abilities and have no purpose in my favorite part of stretching the truth and bounds of credulity when it comes to angling, that being the tall tale.

I have always been amazed how many times the subject of lying or exaggeration arises in fishing writing, with one of my favorite lines concerning this angling failure contained in a piece by Jonah Ogles, “Freddie Doesn’t Do That Anymore” in volume five, issue four of The Flyfish Journal: “He’s a good storyteller, but he doesn’t lie. There’s a difference.”

That’s why I always chuckle when I think back to a couple of stories from a former guide who ran trips in Falmouth. Ironically, this guy’s initials are B.S., but his stories were the best.

One of them concerned false albacore, a species that gets anglers, especially fly rodders, all jazzed up at just the right time in the saltwater fishing season, when the doldrums of August have too often slowed the fishing around the Cape to a crawl.

One of them concerned false albacore, a species that gets anglers, especially fly rodders, all jazzed up at just the right time in the saltwater fishing season, when the doldrums of August have too often slowed the fishing around the Cape to a crawl.

There are the typical exaggerations about albies, with the most common being how much line they run off, similar to the way a bonefish supposedly dumps a hundred yards of backing in the blink of an eye.

But B.S. had something occur that defies imagination. As the story goes, he was fishing for albies around Woods Hole when the weather began to take an ominous turn, with the skies darkening and the wind starting to pick up.

Still, the fish were biting and as anyone who has fished before— especially for albies—will tell you, it’s tough to leave when the action is hot. Suddenly, thunder was upon B.S. and lightning began to spark. A bolt hit the water, causing a pair of albies to leap into the air, whereupon they ran head-on into each other, knocking themselves out.

Believe what you want, but the absolute certainty with which B.S. shared this epic event only added to my admiration of how albies are capable of feats that defy the imagination.

Anyone who has fished the Hole knows that these waters are some of the most productive striped bass fishing waters around the Upper Cape. With a combination of strong currents and rocky structure combining to attract and disorient a variety of fishy food sources, with the menu changing with the season, it is no surprise that anglers flock there.

From swinging flies to jigging parachute jigs on wire line, from tossing topwater plugs to a variety of soft plastics, Woods Hole produces fish, and even when the fish aren’t biting, it’s always an adventure watching inexperienced boaters deal with waters that are called some of the most dangerous in the United States.

From swinging flies to jigging parachute jigs on wire line, from tossing topwater plugs to a variety of soft plastics, Woods Hole produces fish, and even when the fish aren’t biting, it’s always an adventure watching inexperienced boaters deal with waters that are called some of the most dangerous in the United States.

But I digress, because we’re talking about bass here and like their freshwater brethren, the largemouth and smallmouth, stripers orient themselves to structure and no place offers more places for stripers to hang out than the Hole. Anyone who fishes there with any regularity typically learns that while random casting will catch fish, targeting rocks and reefs that allow a striper to hold in calmer water on the downtide side is a prime means of consistently luring a bass into grabbing a lure or bait, including live eels, scup or pogies, with the latter also effective when chunked.

On the particular day when this next event took place, I was talking with Jim Young, manager of Eastman’s, when B.S. came in looking for some piece of tackle. I can’t remember what he was looking for, but he explained to Jim and I that he had located the lair of a monster striper in the Hole and he was going out to catch it.

Sure enough, in what seemed like a couple of minutes but was probably more like a half hour after he left the shop, B.S. marched through the door and informed us that he had, indeed, caught that bass, which he then released.

To this day I have admired B.S.’s ability to call his shot, just as Babe Ruth did in one of the greatest examples of his baseball talents.

We have plenty of species of fish to tangle with around the Cape and islands, but one that never seems to get enough respect is the bluefish. Folks always complain about how they are so easy to catch and too often mess up their tackle.

As a kid who was obsessed with fishing but found no members of his immediate family so inclined to pick up a rod and reel, I learned about how strong bluefish are when I received a rare invite to join a more-distant relative with a boat for some wireline jigging at Horseshoe Shoal. What I experienced was absolute confirmation of what would happen if a big bluefish was tied tail-to-tail with a big bass—the striper would drown.

I discovered that all bluefish, no matter their size, fought like the devil, which often led to some gross miscalculations as to their size.

Nothing convinced me more that bluefish and tall tales go hand-in-hand than what Paul Newmier, former owner of Blackbeard’s Bait & Tackle in Eastham, told me. As I discovered myself, plenty of fishermen are convinced that they have caught a 20-pound or larger bluefish, and during his time working at another tackle shop, Paul said, they had put, as best I can recall when it comes to the amount, a $50 bill on the wall behind the register counter for the first blue that season that tipped the scales at or above that number.

Ultimately, as Paul related, in the decades he worked there, nobody ever claimed that prize, although plenty of folks left the shop with their tails between their legs after what they were convinced was a definite 20-pounder proved to be much smaller, sometimes embarrassingly so.

When it comes to tall angling tales, there are some that don’t even involve catching a fish.

Janet Messineo, a renowned Martha’s Vineyard surfcaster and author of the wonderful autobiographical book, “Casting Into The Light,” said that one year she was casting from the beach at Quansoo on the south side of the island with Bob Lane. They were plug fishing and the surf was really big, with Bob using a yellow darter, a popular, productive design on the island.

Janet Messineo, a renowned Martha’s Vineyard surfcaster and author of the wonderful autobiographical book, “Casting Into The Light,” said that one year she was casting from the beach at Quansoo on the south side of the island with Bob Lane. They were plug fishing and the surf was really big, with Bob using a yellow darter, a popular, productive design on the island.

Bob ended up losing the plug but some time later, despite the heavy surf and stormy conditions, Janet ended up snagging Bob’s lost plug, which she returned as any good angler would. And what are the odds of that—I mean, snagging the plug.

More recently, Janet was walking along a north side beach with a friend who was visiting the island and she mentioned that a couple of years ago she had lost a black-and-purple (a combination commonly called blurple) needlefish plug that someone had made just for her. Janet said that every time she walked this stretch of beach, she would look for that plug.

They ultimately rounded the curve in the beach down toward Tashmoo and her friend discovered a blurple needlefish, which upon examination of the leader knot and other terminal tackle turned out to be the plug Janet had lost over two years ago.

Again, how unlikely is that?

Janet concluded our conversation on tall tales by mentioning, “Did you ever notice that every time someone loses a big fish, it’s always a 50-pounder? You never hear someone say, ‘I lost a big fish, a 25-pounder.’”

When I hung up the phone, I could only laugh at Janet’s observation and appreciate the lengths that anglers go to.