By DEBORAH G. SCANLION

While Woods Hole was not a major Massachusetts fishing port like New Bedford or Gloucester, fishing was a steady presence in the village and surrounding waters for many years.

Native Americans and early settlers often fished the local waters from the shore to provide a major source of sustenance. By the mid-to late 1800s, locally caught menhaden was used for the production of fertilizer at Pacific Guano Company on Long Neck (now Penzance).

In the late 1800s, a popular boat for local fishermen was the iconic Spritsail boat, which handled well especially when the current opposed the wind with the resulting Woods Hole rip tide. The Spritsail was narrow enough to be rowed by one person. And a major advantage was that the Spritsail’s mast could be quickly lowered to fit under the arched stone bridge in Eel Pond where most boats were moored.

In the late 1800s, a popular boat for local fishermen was the iconic Spritsail boat, which handled well especially when the current opposed the wind with the resulting Woods Hole rip tide. The Spritsail was narrow enough to be rowed by one person. And a major advantage was that the Spritsail’s mast could be quickly lowered to fit under the arched stone bridge in Eel Pond where most boats were moored.

Catboats were used by Portuguese fishermen in the 1930s to fish along the Elizabeth Islands. The fishermen would leave their homeport of New Bedford and spend up to two weeks fishing until their boats’ wells were full of tautog, sea bass, cod, mackerel and whatever else was abundant. Doris Vincent Norton, Edgartown native and caretaker at Pasque Island, wrote about them for the Vineyard Gazette. “They seemed to have an uncanny knowledge of wind and weather. Their six to seven months of fishing would earn a living for their families all year.”

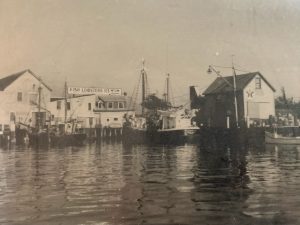

For Woods Hole fishermen, Sam Cahoon’s Harborside Fish Market was a major component in developing a successful commercial fishing business. Cahoon had purchased the market, which was established in 1874 by Isaiah Spindell, from John Nagle in 1915, and became a supporter and friend of local fishermen. Boats would tie up at the market dock—the property is now owned and used by the Steamship Authority—and unload their catch, which at least one time totaled 100,000 pounds, according to his daughter, Frances C. Shepherd, in a Woods Hole Historical Museum (WHHM) conversation in 1981. She also recalled that for a brief time after World War II, boats were not selling their catch to Sam because he did not have radio telephone communication with the fishermen. That changed when a technician from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution helped him install an up-to-date communication systems.

In the book, “Woods Hole Reflections,” authors Robert Livingstone and Margaret Bowles reported there was an increase in the number of young fishermen in the 1930s making Woods Hole their home port. Among them were Warren and Jared Vincent, Henry Klimm Jr., Arthur Nelson and Ken Shepherd, who “acquired larger and more powerful fishing boats, safer and more efficient fishing gear” adding technology like LORAN, radar and radiotelephones after World War II. Captain Warren Vincent’s boat, R.W. Griffin Jr., for example, was launched in 1945, and was 74 feet long, could carry 85,000 pounds of fish, and had a fathometer, direction finder and radio telephone.

In the book, “Woods Hole Reflections,” authors Robert Livingstone and Margaret Bowles reported there was an increase in the number of young fishermen in the 1930s making Woods Hole their home port. Among them were Warren and Jared Vincent, Henry Klimm Jr., Arthur Nelson and Ken Shepherd, who “acquired larger and more powerful fishing boats, safer and more efficient fishing gear” adding technology like LORAN, radar and radiotelephones after World War II. Captain Warren Vincent’s boat, R.W. Griffin Jr., for example, was launched in 1945, and was 74 feet long, could carry 85,000 pounds of fish, and had a fathometer, direction finder and radio telephone.

In a WHHM interview, Captain Klimm estimated that in the 1940s and 1950s, there would be 25 to 30 boats overall coming to Woods Hole to unload their catch at Sam Cahoon’s dock, generally two to three boats daily. Woods Hole was attractive to many fishermen, not just locals, because of its deep waters and convenient location, and the fact that the harbor rarely would ice up. Mr. Cahoon sorted and packed the fish in ice, and transported and sold it to several markets including Boston, New York and New Bedford.

The late John Valois wrote in the WHHM journal “Spritsail” about Sam Cahoon: “In the beginning, Sam got 70 percent of his fish from fishermen who tended the local fish weirs. He bought scup, squid, and scallops caught locally; he bought cod, haddock and pollack caught further offshore…In the spring he bought any mackerel and menhaden that the New Bedford fleets wanted to sell to him on their way home. For the rest he relied on ‘dinner pail boats,’ boats with small gas engines and small dredges that would go out for just one day. But at the end of that one day they would bring back very, very, fresh fish. Yellowtail founder caught off the back side of Martha’s Vineyard was a specialty. Sam had as many as 30 day boats working for him.”

The fishermen were still salting the fish to preserve it, but Sam convinced them that icing was better, Mr. Valois wrote. “So he sent his day boats out with barrels of ice and they came back with barrels of iced yellowtail founder. The catch went from the holds of the boats directly into Sam’s own red and black delivery trucks or onto the trains waiting at the Woods Hole terminal. All those day boats were there every day unloading; it was a very, very fine business to be in. Because Sam’s iced yellowtail founder came to the Boston market fresher than anyone else’s, the restaurant buyers there soon bid up its wholesale price two cents or even three cents a pound at auction.” It was soon labeled “Woods Hole flounder.”

The fishermen were still salting the fish to preserve it, but Sam convinced them that icing was better, Mr. Valois wrote. “So he sent his day boats out with barrels of ice and they came back with barrels of iced yellowtail founder. The catch went from the holds of the boats directly into Sam’s own red and black delivery trucks or onto the trains waiting at the Woods Hole terminal. All those day boats were there every day unloading; it was a very, very fine business to be in. Because Sam’s iced yellowtail founder came to the Boston market fresher than anyone else’s, the restaurant buyers there soon bid up its wholesale price two cents or even three cents a pound at auction.” It was soon labeled “Woods Hole flounder.”

“Other wholesalers in the region found their market share of yellowtail dwindling. Their buyers came to Woods Hole, saw what Sam was doing, and then they renamed their own fish, ‘Woods Hole Flounder.’ Sam said, ‘Ha, ha, that’s the way they want to do it, we’ll do it better!’ and renamed his fish ‘Cahoon Yellowtail Flounder.’…Sam could barely keep up with the Boston market for his yellowtail founder.”

By the late 1800s it became apparent that fish stocks were declining and in 1863, zoologist Spencer Baird came to the village and became aware of the local fishermen’s concerns. He lobbied Congress for funding to address the issue. In June 1871, Baird, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and newly appointed US Commissioner of Fisheries, arrived in Woods Hole to set up the nation’s first fisheries laboratory. Woods Hole had been selected for its deepwater port, its central location and access to offshore fishing sites.

In the next century, local fishermen would help scientists by providing data for their studies. In Henry B. Bigelow and William C. Schroeder’s Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, Part 2 (1953), Captains Jared Vincent and Henry Klimm Jr. are thanked for “furnishing information on the captures of various Skates on the offshore winter fishing grounds off Southern New England.”

There are very few fishing vessels left in the village today, due to a number of reasons that include declining fish stocks, federal regulations and the lack of dock space and markets like Sam Cahoon’s, which closed in 1966 and created a void that was never filled.